Chebyshev's inequality

In probability theory, Chebyshev’s inequality (also spelled as Tchebysheff’s inequality) guarantees that in any data sample or probability distribution,"nearly all" values are close to the mean — the precise statement being that no more than 1/k2 of the distribution’s values can be more than k standard deviations away from the mean. The inequality has great utility because it can be applied to completely arbitrary distributions (unknown except for mean and variance), for example it can be used to prove the weak law of large numbers.

The theorem is named after Russian mathematician Pafnuty Chebyshev, although it was first formulated by his friend and colleague Irénée-Jules Bienaymé.[1] It can be stated quite generally using measure theory; the statement in the language of probability theory then follows as a particular case, for a space of measure 1.

The term Chebyshev’s inequality may also refer to the Markov's inequality, especially in the context of analysis.

Contents |

Statement

Measure-theoretic statement

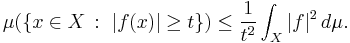

Let (X, Σ, μ) be a measure space, and let f be an extended real-valued measurable function defined on X. Then for any real number t > 0,

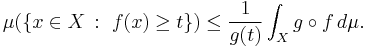

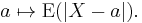

More generally, if g is an extended real-valued measurable function, nonnegative and nondecreasing on the range of f, then

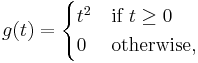

The previous statement then follows by defining g(t) as

and taking |f| instead of f.

Probabilistic statement

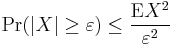

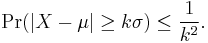

Let X be a random variable with finite expected value μ and non-zero variance σ2. Then for any real number k > 0,

Only the case k ≥ 1 provides useful information (when k < 1 the right-hand side is greater than one, so the inequality becomes vacuous, as the probability of any event cannot be greater than one). As an example, using k = √2 shows that at least half of the values lie in the interval (μ − √2σ, μ + √2σ).

Because it can be applied to completely arbitrary distributions (unknown except for mean and variance), the inequality generally gives a poor bound compared to what might be possible if something is known about the distribution involved.

For example, suppose we randomly select a journal article from a source with an average of 1000 words per article, with a standard deviation of 200 words. We can then infer that the probability that it has between 600 and 1400 words (i.e. within k = 2 SDs of the mean) must be more than 75%, because there is less than 1⁄k2

= 14 chance to be outside that range, by Chebyshev’s inequality. But if we additionally know that the distribution is normal, we can say that is a 75% chance the word count is between 770 and 1230 (which is an even tighter bound).

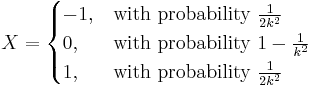

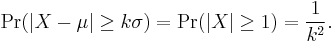

As demonstrated in the example above, the theorem will typically provide rather loose bounds. However, the bounds provided by Chebyshev’s inequality cannot, in general (remaining sound for variables of arbitrary distribution), be improved upon. For example, for any k ≥ 1, the following example meets the bounds exactly.

For this distribution, mean μ = 0 and standard deviation σ = 1k, so

Equality holds exactly for any distribution that is a linear transformation of this one. Strict inequality holds for any distribution that is not a linear transformation of this one.

Variant: One-sided Chebyshev inequality

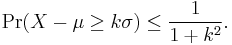

A one-tailed variant with k > 0, is[2]

The one-sided version of the Chebyshev inequality is called Cantelli's inequality, and is due to Francesco Paolo Cantelli.

An application: distance between the mean and the median

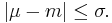

The one-sided variant can be used to prove the proposition that for probability distributions having an expected value and a median, the mean (i.e., the expected value) and the median can never differ from each other by more than one standard deviation. To express this in mathematical notation, let μ, m, and σ be respectively the mean, the median, and the standard deviation. Then

(There is no need to rely on an assumption that the variance exists, i.e., is finite. Unlike the situation with the expected value, saying the variance exists is equivalent to saying the variance is finite. But this inequality is trivially true if the variance is infinite.)

Proof using Chebyshev's inequality

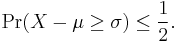

Setting k = 1 in the statement for the one-sided inequality gives:

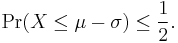

By changing the sign of X and so of μ, we get

Thus the median is within one standard deviation of the mean.

Proof using Jensen's inequality

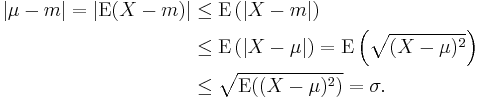

This proof uses Jensen's inequality twice. We have

The first inequality comes from (the convex version of) Jensen's inequality applied to the absolute value function, which is convex. The second comes from the fact that the median minimizes the absolute deviation function

The third inequality comes from (the concave version of) Jensen's inequality applied to the square root function, which is concave. Q.E.D.

Proof (of the two-sided Chebyshev's inequality)

Measure-theoretic proof

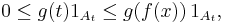

Fix t and let At be defined as At := {x ∈ X | ƒ(x) ≥ t}, and let 1At be the indicator function of the set At. Then, it is easy to check that, for any x

since g is nondecreasing on the range of f, and therefore,

The desired inequality follows from dividing the above inequality by g(t).

Probabilistic proof

Markov's inequality states that for any real-valued random variable Y and any positive number a, we have Pr(|Y| > a) ≤ E(|Y|)/a. One way to prove Chebyshev's inequality is to apply Markov's inequality to the random variable Y = (X − μ)2 with a = (σk)2.

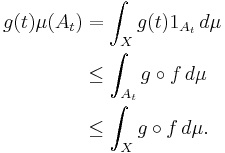

It can also be proved directly. For any event A, let IA be the indicator random variable of A, i.e. IA equals 1 if A occurs and 0 otherwise. Then

The direct proof shows why the bounds are quite loose in typical cases: the number 1 to the left of "≥" is replaced by [(X − μ)/(kσ)]2 to the right of "≥" whenever the latter exceeds 1. In some cases it exceeds 1 by a very wide margin.

Chebyshev's Inequality (More General)

A more general version of Chebyshev's Inequality states:

This version can be proved from Markov's inequality. Also, this version can be used to derive the more specific statement above.

See also

- Markov's inequality

- A stronger result applicable to unimodal probability distributions is the Vysochanskiï–Petunin inequality.

- Proof of the weak law of large numbers where Chebyshev's inequality is used.

- Table of mathematical symbols

- Multidimensional Chebyshev's inequality

References

- ^ Donald Knuth, "The Art of Computer Programming", 3rd ed., vol. 1, 1997, p.98

- ^ Grimmett and Stirzaker, problem 7.11.9. Several proofs of this result can be found here.

Further reading

- A. Papoulis (1991), Probability, Random Variables, and Stochastic Processes, 3rd ed. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-100870-5. pp. 113–114.

- G. Grimmett and D. Stirzaker (2001), Probability and Random Processes, 3rd ed. Oxford. ISBN 0-19-857222-0. Section 7.3.

![\begin{align}

& {} \qquad \Pr(|X-\mu| \geq k\sigma) = \operatorname{E}(I_{|X-\mu| \geq k\sigma})

= \operatorname{E}(I_{[(X-\mu)/(k\sigma)]^2 \geq 1}) \\[6pt]

& \leq \operatorname{E}\left( \left( {X-\mu \over k\sigma} \right)^2 \right)

= {1 \over k^2} {\operatorname{E}((X-\mu)^2) \over \sigma^2} = {1 \over k^2}.

\end{align}](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/536b4b2cc97addd785d6790f02dcd00c.png)